| |

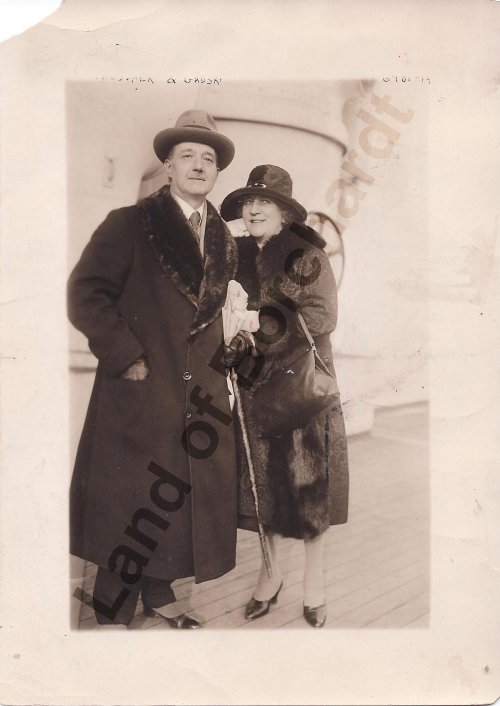

Hans Tauscher was born in Prenzlau, Germany, on October 29, 1867, to a German military officer of the same name, and his wife, Pauline Hillman. Born into a military family, he was in Academies at an early age, and was a Lieutenant in the German army by 1891, the year he attended an opera in Mainz (Mayence), Germany, and heard and saw the already well-known (in Germany), 20-year-old singer named Gadski for the first time. After the performance, he managed to get backstage and ask her to marry him. Startled but instantly smitten, she hesitated, but not for long, and they were married in Berlin, after a secret engagement, on November 20, 1892. A daughter Charlotte, their only child, known all of her life as “Lotte,” was born on August 31, 1893.

The writer, based on cancellations of very important engagements over the next couple of years, believes that the Tauschers tried for other children, but Gadski suddenly was too “indisposed,” the farthest newspapers could go at the time, to make a Bayreuth debut in 1894, a London debut in 1898, etc. It is highly unlikely that a woman would not have wanted to give her husband a son in the 1890’s, so the writer suspects miscarriages were the cause of the very ambitious, reliable, and hard-working Gadski’s “indispositions.”

Their engagement was kept secret because the German Army frowned on its officers marrying “women of the stage,” or those whose positions might open them to public recognition or criticism. Tauscher was told he could marry Gadski, but only if he resigned to reserve status. He resigned immediately.

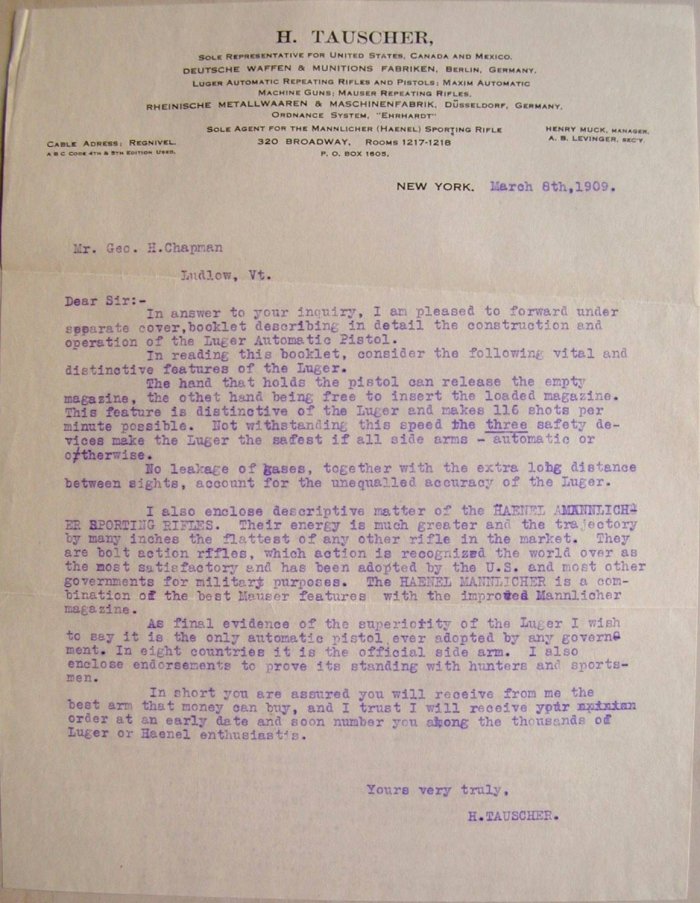

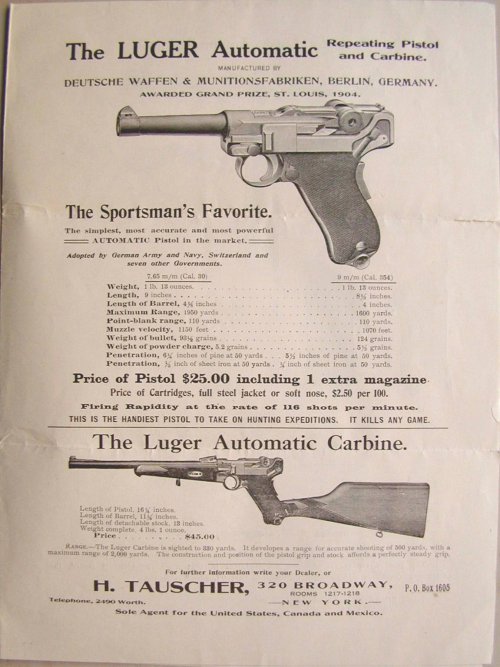

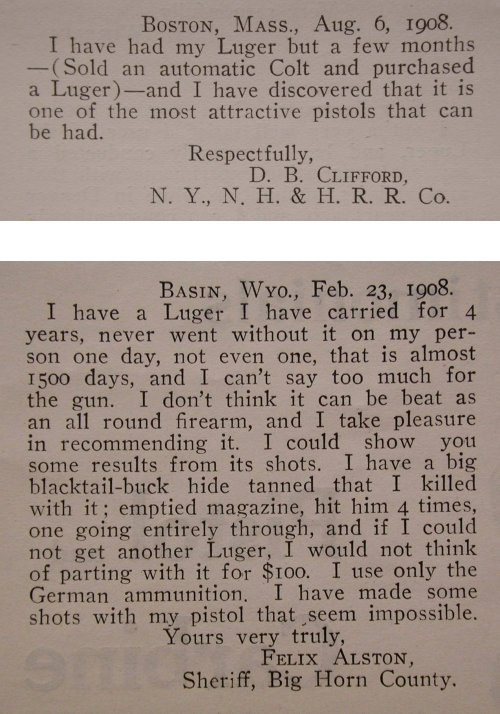

By 1897, when it became obvious that his wife’s career was going to be confined mainly to America, he used his military background, extensive knowledge of ordnance, and fluency in English to convince many German munition and steel concerns to hire him as their chief sales representative in the United States. By 1900, he was comfortably settled in a New York office, and in the ensuing years made millions in his own right by selling Mausers and Lugers to the United States military and police precincts all over the country, as well as dynamite to mining and construction companies, and German steel and iron to the same.

He was gregarious and charming, entertained lavishly, was fluent in six languages and was well liked in New York social and musical circles, as well as by high ranking military representatives in Washington, D. C.

When he returned to the United States in 1914, just weeks after the “Great War” began in Europe, he immediately fell under silent and not-so-silent suspicions, and was carefully “observed” by U.S. officials. In March 1916, England released a condemned to death German spy named Hortz von der Goltz, on the condition that he return to the United States and tell all he knew of “suspicious activities” by resident Germans in the United States, still a neutral country at the time. He immediately named names in an aborted plot to blow up the Welland Canal in Canada, which would have made it almost impossible for American steel to reach Canada and be turned into weapons for Britain (and probably kill innocent Canadians in the vicinity). He named Tauscher as the supplier of pistols and dynamite for the plot. On March 30, 1916, Tauscher was arrested in his New York office, charged with violating United States neutrality laws and “conspiring to launch a military enterprise against the Dominion of Canada” from neutral American soil. Released the same day on $25,000 bail, an astronomical sum in 1916, he faced three years in a Federal prison if convicted. Reporters rushed to his wife with the news before he had a chance to warn her to remain silent on the matter.

"We know nothing as yet of my husband's arrest except through a telephone message from a newspaper,” Gadski told a mob of New York reporters. “ I at once telephoned my husband's office, and the clerk told us that Captain Tauscher had said he would be back for dinner. I don't think he is worrying, and I am sure that we are not.

"The charge against my husband is ridiculous. He is not the kind of man who would do underhand work. As to Von der Goltz, my husband, I am sure, never met him. I think he was Captain von Papen's [Germany’s military attaché] secretary in Mexico. How could he know anything about my husband in America?

"Of course, we know that detectives have been continuously following Captain Tauscher ever since he landed in America, in August, 1914. He is the American agent of the Krupps and the Mausers, and so naturally was considered a suspicious character. But the whole affair is ridiculous. My husband loves America, even if he is a patriotic German. His arrest is the result evidently of the lies told by a bad man."

The reporters pressed for information on Gadski’s own German patriotism, and how far she would go to support the Kaiser. One even asked if she would spy for Germany. Obviously under great stress, she reportedly told the reporters: “I would myself blow up munitions factories. I would give up everything else and go from one plant to another, carrying ruin with me, if only I could warn the workers in time to save themselves. That I would do gladly, and more – for Germany!

“I am a woman. I cannot fight in the trenches. Maybe the ethics of war do not bind my sex so tightly. But, yes – if that is being a spy – I could blow up munitions plants and be glad. I could go from one to another, singing, for I would know that with each one sent into the sky the lives of so many hundreds or thousands of my fellow countrymen would be saved. I would only want to know that I could warn the workers in time to save themselves. There, tell them that!”

Gadski was front page news across the country for weeks. Talk of terminating her contract with the Metropolitan became rampant. When she sang there two nights later, the audience was filled with detectives and undercover, armed policemen, but nothing occurred except very perfunctory applause and a few hisses from the galleries when Gadski took her bows. Critics noted it was obvious that she was a nervous wreck during the performance of the German opera, Wagner’s “Siegfried.”

At his trial in June 1916, Tauscher freely admitted to being in Berlin at the time the War began, and immediately went to German military officials offering his services. He was told to return to the United States immediately, and report to the German Embassy for further instructions. He admitted to selling dynamite and pistols to one of the conspirators who was using an alias and had a genuine looking order from a mining company for the dynamite, but did not know for what purpose the purchase was to be used. He probably did, but the jury believed him, probably because a character reference letter from a high ranking military official in Washington was read in court then dismissed as evidence, and he was acquitted on June 30, 1916. Gadski sat in the court room and wept silently while her daughter comforted her.

Things more or less returned to normal for the Tauschers until February 1917, when the U.S. severed diplomatic ties with Germany. Tauscher was obliged to leave the country immediately, in the company of the German Ambassador and his party. At the sailing, Lotte Tauscher told reporters: “Mother and I will remain under the Stars and Stripes, and we know we will receive ample protection." Newspapers noted that Gadski was the last visitor to leave the ship.

When the U.S. declared war on Germany in April, Gadski’s contract was allowed to expire, and she made her final appearance at the Metropolitan Opera on Friday, April 13, 1917, in Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde.” She and her daughter spent the duration between a rented summer home in New Hampshire, and their New York home on Central Park West, rarely appearing in public, occasionally attending concerts or operas given at theaters other than the Metropolitan, going to movies, and worrying constantly about Tauscher’s whereabouts. When the War ended in November 1918, many Americans claimed to know for fact that Tauscher had done everything in his power to improve conditions for American POWs, and had even pulled strings to get a number of stranded Americans out of Germany.

In 1919, Tauscher asked to be allowed to return to the U.S. with the intentions of becoming an American citizen. He was warned not to enter any territory of the U.S., but by then his wife and daughter were occasionally able to slip away to Cuba, where Tauscher was free to come and go as he pleased.

In 1921 he made the same offer, hinting that he might have secrets about superior German stainless steel and iron he could put to good use as an American citizen in the industry, and he was allowed to return to New York.

He was granted American citizenship in 1925. Gadski, through marriage, became a citizen as well, but was required to sign an oath of allegiance, which she gladly did. Their daughter had returned to Germany as the wife of Ernst Busch, of the Busch brewing family, in 1923.

The Tauschers went to Germany every summer to visit their daughter and grandchildren, and decided to spend Christmas in Germany in 1931. They planned on returning in March, so that Gadski could make arrangements for her German Grand Opera Company’s fourth American tour, but on February 22, 1932, the automobile in which she, Tauscher, their daughter (and a New York friend at the wheel) collided with a street car in Berlin, flipped and capsized. All four where badly injured, but Gadski died at Martin Luther Hospital of massive head injuries shortly after midnight that evening.

Tauscher finally was able to limp ashore in New York from the Hamburg-American liner “Deutschland” in late July of that year, still supporting himself with a cane. "My life is over," he sadly declared to reporters. "I had only one great interest in living and that was in my wife. Now that she is gone, it does not matter much what happens.”

He continued his muntions company till the mid-1930s, then sold his interests and lived quietly in the Central Park West home he and his wife had bought years earlier. He was much feted by New York “society,” but his health began to fail and a nurse/companion/secretary named Marie Brinskele moved into his home in the late 30’s. He died on September 5, 1941, in St. Clare’s Hospital in New York. He was cremated the next day at the Ferncliff Cemetery in New York, and the urn remained there until the mid-1940’s, when it was collected by Ms. Brinskele, presumably to return to Germany, where his beloved wife had been cremated nine years earlier.

|

Home page

Home page